Reviews & Features

Limited Quantity

Call for Availability

508-994-4564

Softcover • ISBN 978-0932027-597 (Limited Supply)

Hardcover • ISBN 978-0932027-566 (Limited Supply / Damaged)

Also available as an eBook!

$9.99

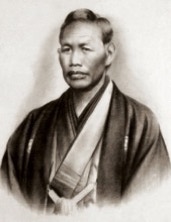

The Man Who Discovered America – John Manjiro Japanese scholars credit Manjiro as the man who introduced Western culture to Japan.

Few Americans know that the bond of friendship between the U.S. and Japan was forged in the nineteenth century by a simple act of kindness between two unlikely individuals–a virtuous New England whaling captain and an adventurous, 14-year-old peasant fishermen.

When Captain Whitfield plucked John Manjiro and his shipmates from the caves of a deserted Pacific Island in 1841, the men were starving, freezing and desperate. A day that began as a fishing trip for mackerel off the southeast coast of Shikuko Island, turned perilous by unforgiving winds, and the men were cast adrift. Eventually, the drifters found refuge on a volcanic island 200 miles off Japan’s coast where they subsisted for seven months until being rescued by the crew of the Massachusetts whaling ship, John Howland.

This dramatic encounter was the beginning of the first friendly contact between the Japanese and American people. Japan had been a closed country for nearly two-and-a half centuries. The poor fishermen had never seen creatures like the burly whalers who rescued them—white men with hairy faces and black men with matty hair.

Unable to bring the castaways back to “that double-bolted nation, Japan”— as Melville referred to Japan in Moby-Dick — the fishermen were brought to Hawaii until arrangements could be made for their return home. At this fateful moment, young Manjiro showed the courage that would exemplify his life from this day on. He agreed to leave his fellow castaways in Hawaii and accepted the invitation of the captain to finish the whaling voyage, then return with him to New England to live with his Christian family.

In Fairhaven, Massachusetts, the captain arranged to have the boy cared for and tutored by family and friends. Manjiro was given a formal education in English, mathematics and navigation. He was apprenticed in the whaling trades and learned to farm and tend livestock. He later signed on as crew aboard a whaling ship and circumnavigated the globe. Manjiro felt forever bonded to the man who saved his life and brought him into his family. Nevertheless, Manjiro longed for his beloved homeland and made plans to leave. He wrote Captain Whitfield who was whaling in the Pacific:

“I never forgot your benevolence of bringing me up from a small boy to manhood…. I hope you will never forget me for I have thought about you day after day. You are my best friend on earth beside the great God…. I believe good will come out of this changing world, and we will meet again.”

In 1849, Manjiro saw his opportunity to return home. Gold fever, which had gripped many young men struggling to make a living at sea, embraced Manjiro and he set out for the California hills. From Fairhaven, he sailed around the Horn and made his way to the mines near Sacramento. Diligent and hard-working, he struck gold. When he earned enough to pay for passage home, he cashed in his claim and set sail for Oahu where he would reunite with his fellow castaways. Two of the men were eager to join Manjiro for the trek home even though they would risk execution under the country’s strict isolation policies upon their return.

Their timing was good. Japanese officials caught wind of the impending arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry’s squadron of “Black Ships” at Yokahama Harbor. This historic event occurred just several months after the castaways landed on the beach of Okinawa, marking the end of their 10-year odyssey abroad. Under Perry, the Americans demanded that Japan open her ports, and Manjiro proved useful to the government with his knowledge of Western ways. His stories of steam engines, locomotives, telegraphs, and democracy were almost too fantastic to believe. But evidence of the West’s military might, maritime prowess, science and technology, made it clear that the young castaway had great knowledge—and he was eager to give it to Japan.

Manjiro would play a significant role on the world stage for his country. He joined Japan’s first delegation to America and Europe. He taught English, navigation, whaling, maritime trades, and earned a teaching position at the University of Tokyo. He deeply influenced the pioneers of modernization in Japan, such as Sakamoto Ryoma and Yukichi Fukuzawa, and was made a samurai scholar by the ruling shogunate. These were extraordinary accomplishments for a poor, uneducated boy from a small Japanese fishing village.

Manjiro’s legacy continues to be felt in the 21st century. The enduring friendship between Nakahama Manjiro and Captain Whitfield has been nurtured in their descendants, outlasting two World Wars, civil wars, rebellions, economic crisis, and half the breadth of the world. The families of the two men meet once a year at the Grass Roots Summit held alternately in each country. It is attended by hundreds of people interested in advancing the spirit of peace and friendship that began over 160 years ago with Whitfield’s simple act of kindness, and Manjiro’s decisive show of courage.

Junya Nagakuni and Junji Kitadai have long been engaged in the study of Manjiro and his historical impact on shaping Japan’s view of the world. Both men were born and raised in Manjiro’s home district in Kochi Prefecture, Japan.

Junya Nagakuni is President and Managing Director of Nichibei School of Foreign Languages in Kochi City, Selborne High School and College in Ino, and Susaki Business College in Susaki. He is the author of numerous books, including The Sea of Great Ambition, The Illustrated Story of John Manjiro, and All About John Manjiro. Mr. Nagakuni gives a series of lectures throughout Japan on important historical figures such as Manjiro, Sakamoto Ryoma, and Baba Tatsui. He has an M.A. in Economics from Aoyama Gakuin University in Tokyo.

Junji Kitadai has more than 40 years experience in broadcast journalism both in Japan and the United States as a correspondent and news executive. He began his career as a news reporter for the Tokyo Broadcasting System, and later served as Washington Correspondent, New York Bureau Chief, Foreign News Editor and Anchorman. Mr. Kitadai received his M.S. from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and in 1988 was the recipient of the “Columbia Alumni Award for a Distinguished Career in Journalism.”

Mr. Kitadai wrote the Epilogue in Drifting Toward the Southeast entitled “The Legacy of Manjiro,” which traces Manjiro’s life after his return to Japan, and the former castaway’s influence in Japan’s dynamic development toward openness to the West. Based in New York, Mr. Kitadai is currently working on a new book about the life and times of Nakahama Manjiro.

Junji Kitadai (left)

and Junya Nagakuni